The War on Drugs Project

In 2020, CMWSS hosted a symposium entitled “The War on Drugs: Fifty Years, a Trillion Dollars, and Thirty Million Arrests.” This page is a companion to the newly published volume The War on Drugs: A History, edited by David Farber, and features material created by Clark Terrill and designed by Marjorie Galelli. It includes a teaching guide for each chapter, containing both questions and a list of key terms and themes; a timeline for the war on drugs; and a list of primary sources useful for teaching about this topic.

War on Drugs Teaching Guide

Part I: Background

Introduction and The Advent of the War on Drugs

-

Offender-to-prison pipeline

Mass incarceration/carceral state

Counterculture and conservatism

Decriminalization

Racial discrimination in the war on drugs

-

How has public opinion regarding drugs shifted since the early twentieth century, and why? How, and to what extent, has policy changed to reflect (or counteract) such shifts?

According to Farber, how do the “sunk costs” of the war on drugs help to perpetuate it? What kinds of organizations or industries have an economic interest in continuing a punitive war on drugs?

How have the (perceived) demographics of drug users affected the timing and implementation of drug policy? Which groups are identified as dangerous, and which are singled out as needing protection from drug peddlers?

Part II: Supply and Demand

Drug Dealers

-

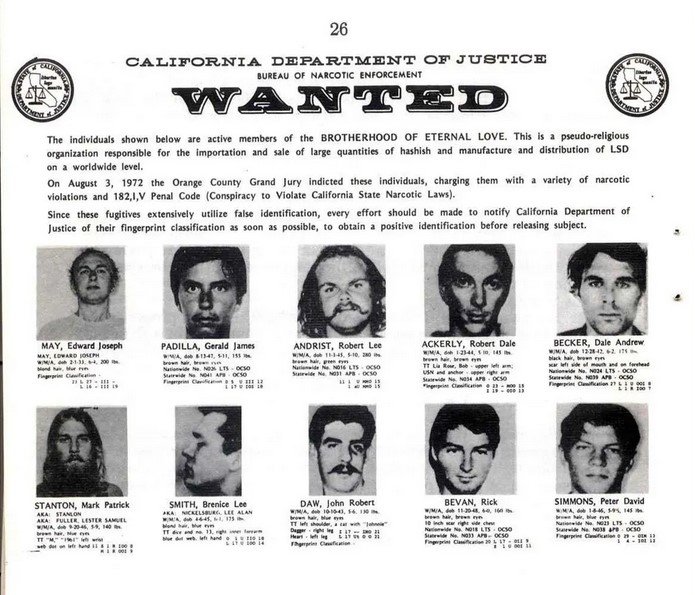

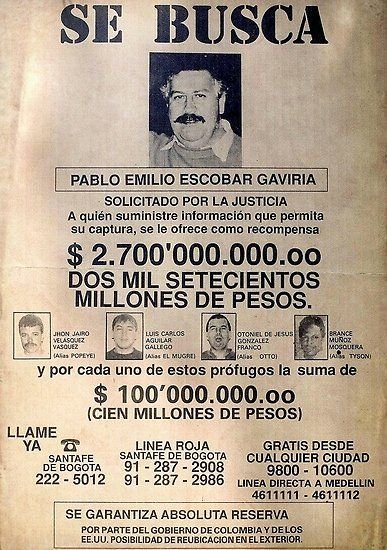

Organized crime, Brotherhood of Eternal Love, Coronado Company, Felix “The Cat” Mitchell, Darryl “Lil D” Reed

Popular support for war on drugs

“Social bandits”

Gangsta rap and “flossing”

“No snitching”

-

Farber describes an increasing level of violence in the drug trafficking business over the course of the 1970s and into the 1980s. How might one explain the decline of the “Robin Hood era of dope dealing,” and its replacement by a more violent and capitalistic drug trade?

What incentives does Farber identify as appealing to illicit dealers and trafficking organizations? What are “social bandits,” and how does this concept explain the elevated status of the drug dealers described in this chapter?

What strategies did these dealers and organizations deploy in order to scale up distribution and market their products?

What are some common characteristics of the drug traffickers described in this chapter? In what ways are they different from one another, and what social or economic context might account for those differences?

The Mexico–Chicago Heroin Connection

-

Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs), transnational smuggling

1973 Chicago Police raid, investigation into Herrera DTO’s structure

Comprehensive Criminal Control Act of 1986

Inclusion of women in DTOs

Operation Durango

-

What advantages does Carey identify with the Herrera Drug Trafficking Organization’s transnational network?

How does the Herrera DTO differ from the organizations described by Farber in the previous chapter? What characteristics do they share?

According to Carey, how did the investigation of the Herrera DTO and similar organizations inform the Comprehensive Criminal Control Act of 1986? How did this legislation affect law enforcement in the war on drugs?

Cultivating Cannabis, Excepting Cannabis

-

Cannabis exceptionalism

Crop substitution and developmentalism

Prohibition premiums

Counterculture, Back-to-the-land movement

Medicalization and patient-activists

-

How does Polson explain “cannabis exceptionalism,” and what is his objection to it?

What has been the role of colonialism and of “bourgeois nationalism” in the globalization of cannabis prohibition?

Polson describes cannabis cultivators as a “distinctively modern global peasantry.” What policies, on the part of the United Nations as well as specific member nations, created this emergent class, and what made it “distinctively modern”?

Using Polson’s case study of Northern California as an example, how have the histories of domestic and foreign growers diverged? What are the potential consequences of treating domestic cultivation as exceptional in a broader war on drugs?

Part III: The Domestic Front

The Local War on Drugs

-

“Second ghetto,” residential segregation

Mayor Richard M. Daley’s punitive approach, Assistant District Attorneys, influence on Illinois law

Mayor Harold Washington’s “rainbow coalition,” calls for police reform, drug abuse prevention and rehabilitation, hostility of city council, response to gang violence

Chicago Police Department, 1982 Illinois Narcotics Forfeiture Act

“Class X” felonies

Emergence of crack cocaine, exacerbating punitive trends

-

Pihos describes how, in Chicago, “local law enforcement created three different local drug regimes.” How does the author periodize the local war on drugs, and how did city officials come to embrace a “state of war on gangs and drugs”?

In his conclusion, Pihos argues against locating the origin of mass incarceration in Great Society liberalism. What alternative explanation(s) does the author offer? What factors converged in the 1980s to contribute to mass incarceration?

Cannabis Culture Wars

-

Cannabis use by middle-class youth, state-level decriminalization in the 1970s

Cannabis paraphernalia, youth-oriented marketing

Marsha “Keith” Schuchard and Thomas “Buddy” Gleaton, Parents’ Resource Institute for Drug Education (PRIDE), Sue Rusche, Families in Action

High Times

Keith Stroup, NORML, controversy over paraquat spraying

Jon Gettman, NORML’s 501(c)4 status and engagement with parents’ concerns

National Federation of Parents for Drug-Free Youth

-

How did parent-activists approach the problem of youth drug use? What avenues did they pursue to combat this threat?

Were legalization advocates able to reconcile their arguments with the concerns raised by the parents’ movement? If so, how?

Psychedelic Wars: LSD as Mental Medicine in a Battle for Hearts and Minds

-

Researchers’ struggle for legitimacy

Oscar Janiger and Sidney Cohen’s divergent attitudes toward psychedelic treatment

1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments

Carol Chertkow’s research into users’ attitudes toward psychedelics

-

What are “insider accounts,” and what is their role in what the authors call “historiographical wars” over psychedelics?

What challenges did advocates of LSD and other psychedelics encounter from regulatory agencies, mainstream culture, and other researchers?

Part IV: The International Front

The War on Drugs in Mexico

-

Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), suppression of dissidents and guerrillas, Tlatelolco massacre

Operation Intercept

Crop eradication, U.S. financial and material aid to Mexican military and law enforcement

Federal Security Directorate (DFS)

Guadalajara cartel

U.S. interagency rivalry

National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) 221

Manuel Buendía and Enrique “Kiki” Camarena, Operation Leyenda

-

To what extent has the Mexican government aligned its policies with U.S. objectives in the war on drugs, and why?

How, according to the author, did the PRI use a U.S.-subsidized war on drugs to buttress its social and political control of Mexico?

Teague frames the Mexican government's adoption of a militarized war on drugs, in part, as a response to potential U.S. encroachment on Mexican "sovereignty." How does a globalized war on drugs threaten the sovereignty of countries where drug crops are cultivated?

What was the role of drug cultivation in the growth of anti-PRI guerrillas' power in rural Mexico?

The War on Drugs in Afghanistan

-

Terry Burke, Brotherhood of Eternal Love, opium supplanting cannabis

Helmand development project, USAID, UN Fund for Drug Abuse Control

1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

Qawm and rural/peripheral enforcement of drug laws

Crop substitution and eradication

Muhammad Daud Khan

-

How did development aid contribute to the emergence of opium as a major cash crop in Afghanistan?

How did different levels of the government of Afghanistan respond to the United States' efforts to internationalize the war on drugs?

How does the war on drugs in Afghanistan compare to the war on drugs in Mexico? How would you characterize these countries' relationship with the United States?

Part V: “The Alternative to War”

Between the Free Market and the Drug War

-

Black markets and “white” markets

Kefauver-Harris Amendments, Controlled Substances Act

State-level regulation, Controlled Substances Boards, Diversion Investigation Units

Third-wave consumer advocacy

Production quotas

Privileged categories of drug users, racial discrimination in prescribing

-

What was the effect of consumer advocacy on drug regulation? How did consumer advocates differ from “addiction medicalizers?” To what extent did the Controlled Substances Act accommodate the concerns of both groups, as well as those of hardline anti-drug crusaders?

How did the 1970 legislation reinforce a racial logic underlying the distinction of medical drug use from illicit drug "abuse"?

The Pharma Cartel

-

Neoliberalism

“Revolving door” between regulatory agencies and private industry

Mallinckrodt, Purdue Pharma, Noramco (Johnson & Johnson)

Prescription Drug User Fee Act and FDA budget

Opioid supply lines, “80–20 rule”

DEA solicitation of manufacturer input on quotas

-

Frydl largely attributes the opioid crisis to the ascendancy of neoliberalism. How does the author explain the effects of deregulation and privatization on the supply of opioids to both pharmacies and illicit users?

Frydl argues that “condemning the Sackler family [of Purdue Pharma] means characterizing them as aberrational.” What, according to the author, is the danger of framing the opioid crisis in such a way? Do you agree?

Summary Question

When, where, and why did war become the dominant metaphor guiding drug policy?

Selected Primary Sources

“Negro Cocaine Fiends,” New York Times article (1914); Stories such as this reflected racist stereotypes of drug users, rather than any documented phenomenon.

Statement of Harry Anslinger before a Congressional committee considering the Marihuana Tax Act, as well as additional materials entered into the record (1937).

Timothy Leary coined the phrase “Turn on, tune in, drop out” in this monologue, detailing his early experiments with LSD and his thoughts on the potential of psychedelics. (1966)

Sidney Cohen, The Beyond Within (1964, second ed. 1967); Cohen was an early researcher of, and advocate for, the therapeutic use of LSD.

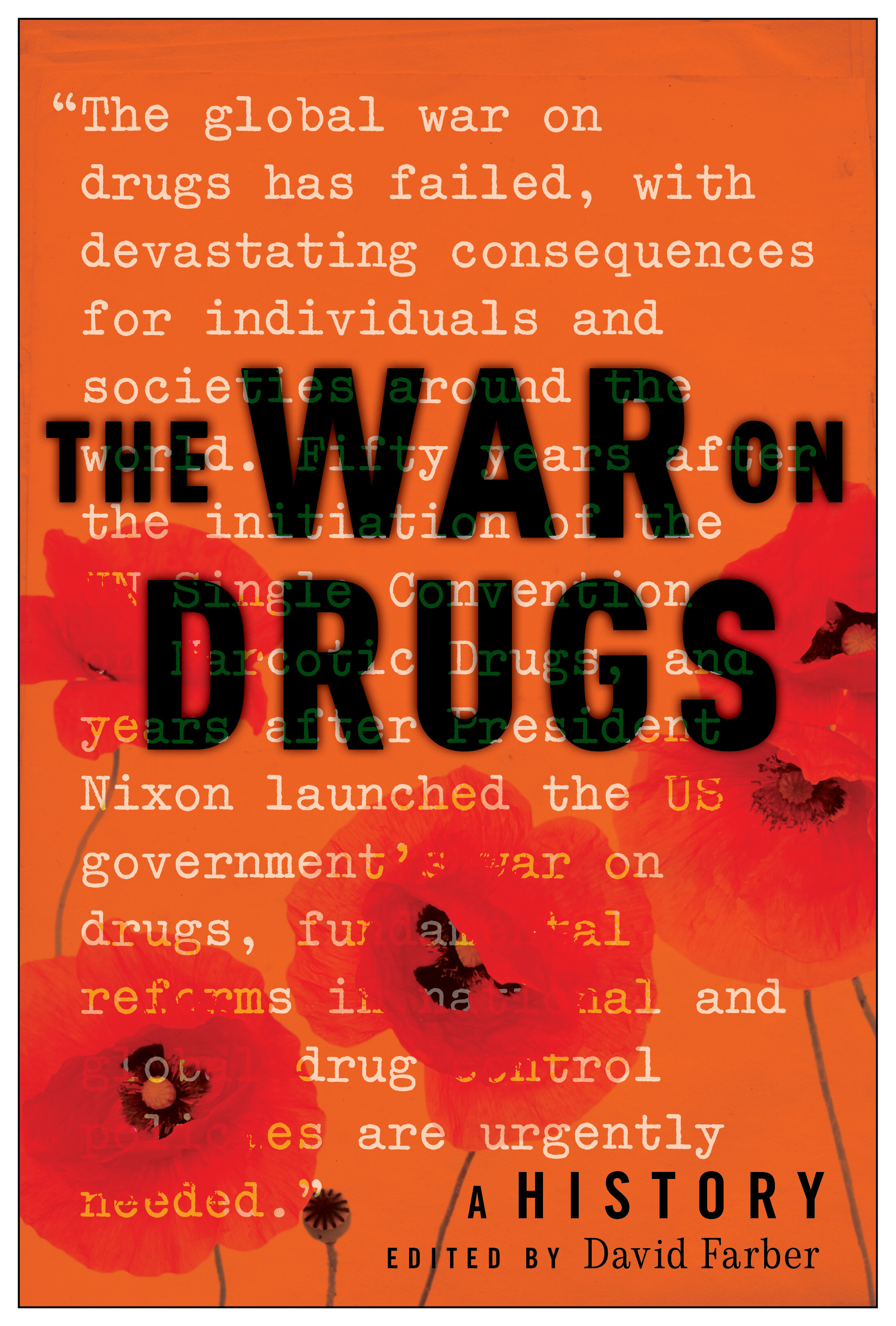

An advertisement for Serax, a drug for treating anxiety. (1967); Many pharmaceutical advertisements of the 1950s and 1960s highlighted a perceived need for medication of overstressed housewives.

A live televised debate between Timothy Leary and Jerome Lettvin concerning LSD (1967)

Excerpts from a report by a Nixon administration task force on drug trafficking across the U.S.-Mexico border. (1969)

President Nixon calls for an “all-out offensive” against drugs (1971) Video

White paper on drug abuse, (1975)

“Satellites Used to Round Up U.S.-Bound Marijuana Ships,” Washington Post article (1978).

Marsha “Keith” Schuchard, “Parents, Peers, and Pot” (1979); Schuchard, a prominent parent activist, wrote this pamphlet for the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

[WARNING: SEXUALLY EXPLICIT LYRICS] N. W. A., “Dope Man” (1987)

Too $hort, “The Ghetto” (1990)

Senators Biden, Hatch, and Gramm, remarks on the 1994 Crime Bill (doc 1; doc 2) (1994)

President Clinton’s remarks on signing the 1994 crime bill (1994)

[WARNING: SEXUALLY EXPLICIT LYRICS] Notorious B. I. G., “Ten Crack Commandments” (1997)

Court decision regarding Purdue Pharma’s role in the opioid crisis. (2020)

Drug Wars Timeline

1881-2020

1881

Kansas becomes the first state to ban the sale and manufacture of alcoholic beverages.

1897

Chemists working for the German company Bayer synthesize both acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) and diacetylmorphine (heroin) within a week of each other. The latter is initially intended as a substitute for morphine, with less potential for dependency.

1906

The Pure Food and Drug Act bans the interstate transport of drugs considered “adulterated” by the addition of harmful chemicals. Responsibility for enforcement is placed with the Bureau of Chemistry within the Department of Agriculture – later renamed the Food and Drug Administration.

1909

Congress bans the non-medical distribution of opium, enshrining a distinction between legal (medical/pharmaceutical) and illicit distribution of a given substance.

A display of various medicines containing opium or its derivatives and intended for infants. After the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, such medicines were required to list their ingredients; before 1914, however, the inclusion of cocaine or opioids was not restricted by federal law. National Library of Medicine. c. 1910.

1911

Massachusetts becomes the first state to prohibit the non-medical use of cannabis.

1912

The United States bans absinthe, a distilled spirit believed at the time to be hallucinogenic. The ban remains in effect until the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau rescinds it in 2007, when parties interested in importing the beverage to the United States demonstrate its safety.

1914

The Harrison Narcotics Act introduces the first comprehensive regulatory regime for controlling drugs at the federal level. The Act, which targets cocaine and opioids (including opium, morphine, codeine, and heroin), places the responsibility for their regulation in the Treasury Department by means of a special tax.

The first raid on cannabis growers in the United States occurs in Los Angeles.

1919

The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution is ratified, outlawing the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. Prohibition goes into effect January 17, 1920.

1922

The Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act greatly limits the legitimate importation of opiates and cocaine into the United States, contributing to the growth of underground trafficking operations.

1930

An Act of Congress establishes the Federal Bureau of Narcotics within the Treasury Department. Harry Anslinger, its first commissioner, retains his position as head of the Bureau until his retirement in 1962.

1934

The FBN begins campaigning for states to adopt the Uniform Narcotic Drug Act, which includes tighter restrictions on narcotics than are provided in the Harrison Narcotics Act.

1937

Congress passes the Marihuana Tax Act to restrict the possession, transportation and distribution of cannabis. Harry Anslinger, chief of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, campaigned for such legislation with articles in which he attributed a multitude of violent crimes and cases of insanity to the drug.

1938

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which grants the FDA authority to ensure the safety of drugs and other products, passes Congress.

1944

Afghanistan bans government-run production of opium. In return for the ban, the United States agrees to formalize its diplomatic relationship with Afghanistan.

1949

Harris Isbell and V. H. Vogel publish research showing methadone to be effective for treating opioid withdrawal symptoms. Their protocol of administering decreasing doses over the course of a week or more is adopted by several institutions, though follow-up studies show discouraging recidivism rates.

1951

Congress passes the Boggs Act, which amends the 1922 Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act to specify mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. A 1956 statute raises these minimum sentences further, as well as allowing for juries to impose the death penalty for the sale of heroin by an adult to a minor.

Illinois passes a measure providing for harsher mandatory sentences for drug possession, and the Chicago Police increases its Narcotics Section from four to sixty officers, in an early step toward a more punitive war on drugs.

1953

CIA director Allen Dulles delivers a speech on the threat of Communist brainwashing. Three days later, Dulles authorizes Project MKUltra, the CIA’s own investigation into brainwashing and interrogation with the assistance of psychoactive drugs such as LSD.

1956

In the Narcotic Control Act of 1956, Congress declares heroin, in all instances, to be contraband.

The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA, later the MPAA) revise the Hollywood Production Code (“Hayes Code”) to allow the depiction of drug use onscreen.

1957

Gordon Wasson, a vice president at J. P. Morgan, writes an article for Life detailing his experiences with psychedelics.

Afghanistan begins limited enforcement of a blanket ban on opium.

1961

The United Nations adopts the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. With the aim of standardizing the control of various illicit and pharmaceutical drugs, the Single Convention organizes drugs into several “schedules,” or levels of restriction, taking into account their potential for addiction and harm.

1962

Congress passes the Kefauver-Harris Amendments to the 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, establishing new requirements for the approval of drugs before they go to market. The FDA begins confiscating LSD from researchers, pursuant to the new legislation.

1963

Diazepam, brand name Valium, is introduced to the market. By the mid-1970s, it is the most commonly used drug in the United States.

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics establishes a small office in Mexico City, with a focus on monitoring the Turkish-French heroin smuggling ring.

1965

Congress passes the Drug Abuse Control Act, which tightens restrictions on prescription drugs and authorizes the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to add drugs to the law without Congressional approval.

Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander publish an article on the use of methadone for the long-term treatment of heroin addiction, initiating a rapid expansion of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs, and research into their effectiveness, over the next decade.

1966

The Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act, which enables some drug users to undergo supervised treatment rather than imprisonment, passes Congress.

1967

Timothy Leary, an advocate for the consciousness-expanding potential of psychedelics, coins the phrase “turn on, tune in, drop out” in a speech at the “Human Be-In,” a hippie gathering at Golden Gate Park, San Francisco.

1968

While on the campaign trail in Anaheim, California, presidential candidate Richard Nixon announces that, if elected, his administration will step up drug interdiction efforts.

1969

President Nixon authorizes Operation Intercept, all but shutting down U.S. Mexico border crossings for seven weeks to inspect all travelers for drugs. Joe Arpaio, future sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona, takes part in the operation, as does Nixon advisor G. Gordon Liddy.

According to a Gallup opinion poll, 84% of Americans surveyed support jail time for marijuana possession.

1970

Congress passes the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), which introduces the modern “schedules” for regulating different categories of drugs. The CSA provides for greater consumer protections against the pharmaceutical industry and increased federal support for addiction treatment, but also reinforces the criminalization of illicit drug use.

Attorney Keith Stroup founds the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), using $5,000 in funding from the Playboy Foundation. The organization is a major advocate for cannabis legalization in the following decades.

1971

Amidst concerns over high rates of drug use, especially among youth, and with regard to heroin in particular, President Richard Nixon calls for an “all-out offensive” to eliminate the trade in illicit drugs, the consumption of which he characterizes as “public enemy number one.” The phrase “War on Drugs” quickly catches on. In July, the president establishes the Special Action Office on Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP) by executive order.

The French Connection portrays a battle between law enforcement and heroin smugglers, and The Panic in Needle Park dramatizes the precarious lives of heroin users in New York City.

1972

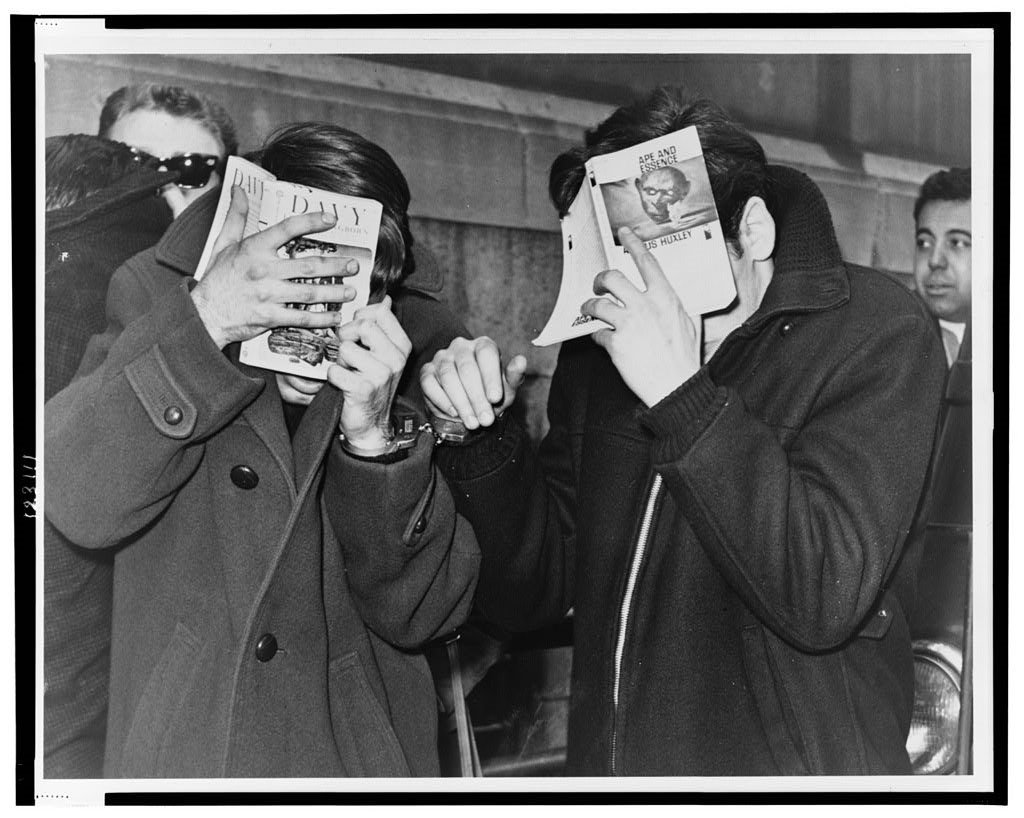

Fifty-three members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love are arrested in raids across Hawaii, California, and Oregon. The Brotherhood was a loose affiliation of international drug traffickers, originally based in Southern California and primarily dealing in LSD, cannabis, and hashish.

The National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse delivers a report to President Nixon, arguing that the use and possession of cannabis should be decriminalized.

Texas, Michigan, and Alabama are the first states to establish Diversion Investigation Units to combat the diversion of pharmaceuticals to illicit markets.

1973

Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York launches a campaign to enact harsher penalties for drug offenses. In spring, the state legislature passes the “Rockefeller Drug Laws,” including provisions for mandatory sentences of fifteen years to life for the sale or possession of significant quantities of drugs for a first offense, and twenty-five years to life for a second offense.

Twenty-five members of the Herrera drug trafficking organization are arrested by the Chicago Police Department’s gang unit. Police seize roughly one million dollars’ worth of drugs, mostly heroin.

Oregon decriminalizes possession of small amounts of cannabis.

1974

Tom Forçade publishes the first edition of High Times, a magazine centered on the cannabis lifestyle. High Times collaborates with NORML on pro-legalization messaging.

1975

A white paper commissioned by the Ford administration finds that the decline in illicit drug use observed in the early 1970s “was, in the main, temporary and regional,” and recommends greater focus on interrupting the supply of drugs.

1976

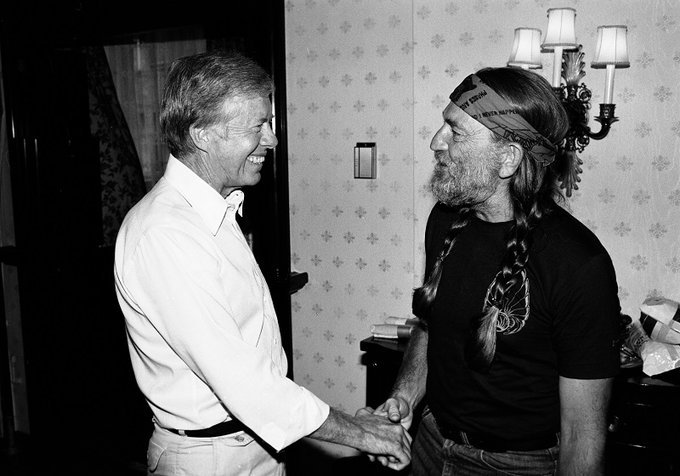

Jimmy Carter becomes the first presidential candidate to announce his support for decriminalizing the possession of cannabis.

1977

The Illinois legislature establishes a new category of “Class X” felonies, subject to harsher penalties and mandatory prison sentences.

1978

The Carter administration cools on federal decriminalization after the resignation of Peter Bourne, Special Assistant to the President on Drug Abuse, amidst allegations of writing an illegal prescription for Quaaludes, as well as using cannabis and cocaine at a NORML party.

Annual sales of the popular benzodiazepine Valium peak at nearly ninety million bottles – roughly 2.3 billion pills.

1979

Marsha “Keith” Schuchard and Thomas “Buddy” Gleaton found the Parents’ Resource Institute for Drug Education (PRIDE), a national network of parents opposed to marijuana use among children and adolescents. Schuchard writes a guidebook, titled Parents, Peers, and Pot, for the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

1982

First Lady Nancy Reagan coins the slogan, “Just Say No,” for a nationwide campaign to discourage drug use among children and adolescents.

Former Nixon advisor and convicted Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy joins LSD advocate Timothy Leary on a debate tour of college campuses.

1983

The California Department of Justice launches the Campaign Against Marijuana Planting (CAMP), aimed at eradicating cannabis crops in California.

The Los Angeles Unified School District, in collaboration with the LAPD, implements Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.), a program in which schools invite police officers to deliver a standardized curriculum on illicit drugs to primary and secondary school classrooms.

1984

Congress passes the Comprehensive Criminal Control Act to combat organized drug trafficking. The Act provides for expansive federal and civil asset forfeiture penalties, which incentivize enforcement agencies to seize property and funds through raids and arrests of drug traffickers.

Mexican authorities raid the El Búfalo marijuana plantation in the largest-ever seizure of cannabis at the time. The action provokes retaliation from the Guadalajara Cartel, which abducts and murders a DEA agent three months later.

1985

DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena is kidnapped and killed by the Guadalajara drug trafficking organization, prompting an investigation by the DEA called Operation Leyenda. Leyenda results in convictions of mostly low- and mid-level Mexican traffickers, though with several prominent members of the Guadalajara Cartel arrested over the next four years.

The United States federal and state prison population surpasses half a million individuals.

1986

Basketball star Len Bias dies after snorting cocaine, prompting lawmakers to take action on both powder and crack cocaine.

Congress passes the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which introduces a 100:1 sentencing disparity for the possession of crack vs. powder cocaine. This disparity contributes to the disproportionate incarceration of poor, mostly black, users of crack cocaine over the following decades.

The Reagan White House issues National Security Decision Directive 221, which defines the international drug trade as a legitimate threat to national security.

1987

At the height of the crack cocaine crisis, a Gallup poll finds thirty-eight percent of Americans support capital punishment for convicted drug dealers.

1988

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 establishes criteria for applying the death penalty to certain drug-related offenses.

1989

The administration of President George H. W. Bush orders the DEA to set up a crack purchase in Lafayette Square, across from the White House. The sting is planned and executed after the president’s speechwriters come up with the idea in order to make a rhetorical point about crack being sold so near to the White House. Keith Jackson, 19, is arrested for selling the drugs and is sentenced to ten years in prison.

In December, President Bush cites drug trafficking as a proximate cause of the United States’ invasion of Panama, codenamed Operation Just Cause.

Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo, leader of the Guadalajara Cartel, is arrested for the 1985 murder of Enrique Camarena.

1990

The United States launches Operation Green Sweep, deploying soldiers from the Army’s 7th Infantry Division to Northern California in raids on cannabis growers.

1992

Congress approves the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, which requires pharmaceutical companies to pay an application fee for the approval of new drugs. The Act aims to speed the approval process and supplement the FDA’s budget.

1994

Congress passes the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, commonly referred to as the 1994 Crime Bill. The Act provides for grant incentives for states to enforce mandatory minimum sentences, as well as allowing the death penalty for certain “non-homicidal” narcotic offenses.

1995

The FDA approves OxyContin, an opioid analgesic patented by Purdue Pharma. The company’s insistence that the drug’s time-release coating would prevent patients from developing a dependence, in conjunction with a strategy of aggressive marketing and illegal kickbacks, leads physicians to underestimate the dangers of OxyContin. The prescription of large quantities of the drug contributes to the beginning of the ongoing opioid crisis in the mid-1990s.

In August, the Coast Guard seizes twelve tons of cocaine bound for California. This record, for the largest maritime seizure of drugs, holds until 2007, when the Coast Guard finds approximately 23.5 tons of cocaine aboard a Panamanian container ship.

1996

California becomes the first state to legalize the medical use of cannabis.

2000

Plan Colombia, which provides for U.S. aid to Colombia to combat insurgents and drug traffickers, is signed into law.

The Department of Education announces it will no longer allow federal funds to go toward implementing D.A.R.E., after a 1999 ten-year longitudinal study confirms previous studies’ findings: that the curriculum has a negligible impact on students’ attitudes toward drugs.

2002

Mexico’s Policía Judicial Federal (PJF) disbands due to extensive cooperation between drug trafficking organizations and its own agents.

2004

A Portland Sheriff’s deputy creates the “Faces of Meth” campaign, which distributes mugshots of arrestees, presumed to be meth users, for publication and dissemination.

2009

The United States prison population (state and federal) peaks at more than 1.5 million incarcerated individuals, and gradually declines over the following decade.

D.A.R.E., still implemented in seventy-five percent of American schools, reformulates its curriculum to model it on other, evidence-based programs.

2010

The Fair Sentencing Act reduces the sentencing disparity between powder and crack cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1 in an effort to reign in mass incarceration.

2012

Colorado and Washington become the first states to legalize the recreational use of cannabis.

2016

Sinaloa Cartel leader Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán is arrested by Mexican authorities, having previously escaped prison and evaded capture, and is extradited to the United States.

2019

The first U.S. Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research is established at Johns Hopkins University.

2020

Purdue Pharma pleads guilty to three felony counts of criminal wrongdoing relating to its marketing of OxyContin, agreeing to a bankruptcy settlement of about $8.3 billion, as well as to being restructured as a public benefit corporation. The Sackler family, which owns the company and possesses an estimated net worth of $13 billion, agrees to pay $25 million in civil penalties.

The Oregon legislature approves a bill to decriminalize possession for all drugs.

With measures passed in Arizona, Montana, and New Jersey, non-medical cannabis is legal in fourteen states.